The Voice

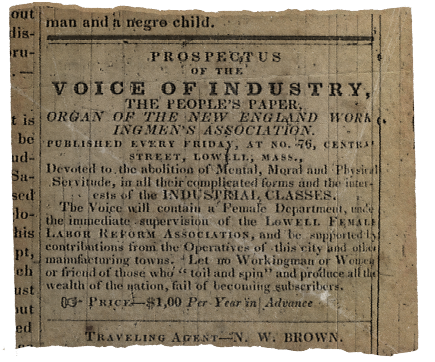

The Voice of Industry was the longest running labor newspaper published during the American Industrial Revolution, and one of the most widely read of the many lively worker-run journals of the period.* It started publication on May 29, 1845 in Fitchburg, Massachusetts under the auspices of the New England Workingmen’s Association, with young mechanic William F. Young at the helm. Written and published by the workers themselves, the Voice was concerned with the dramatic social changes that were taking place as corporations began to dominate economic life.

While primarily interested in labor reform, the Voice cast a much wider net. “With all systems of oppression, we shall do battle,” declared Young in his inaugural editorial. “All matters touching the well being of the community…will come under our cognition.”

Indeed, the paper addressed itself a number of issues, including education, women’s rights, Christianity, slavery, capital punishment, and the Mexican war. All of the writing was done by the “workingmen and women” themselves, who, as Young wrote, “can wield the pen with as much perfection as the instruments of their respective vocations,” and to whom he extended “a hearty welcome...whether they agree with us on all points or not.”

Workingmen

Publishing a Paper?

To the Factory Girls

A Singular Medley

Introducing

the Voice

click to expand

New Newspaper Head

Servility of the Press

Call for Subscribers

To the Patrons

The Voice Sails On

The Association

Buys The Voice

A Few Advertisements

On The Road

for The Voice

Selling The Voice

to Mill Hands

—

Editors and

Honorable Mentions

click to expand

—

The Lowell Offering: Mouthpiece of the Corporations?

click to expand

—|—

Female Department

click to expand

The prospectus of the Voice, declaring the paper's devotion to “the abolition of Mental, Moral and Physical Servitude, in all their complicated forms and interests of the INDUSTRIAL CLASSES." From an 1846 issue.

the voice of female labor

Shortly after it was established, the Voice moved to Lowell, Massachusetts, where its publishing committee was expanded to include Sarah Bagley, then president of the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association, the first union of workingwomen in America.

Under Bagley's influence, the paper became the official herald of the Association, and entreated the workingwomen of Lowell to make the Voice their own. “It is your paper, through which you should be heard and command attention,” she wrote. “The Press has been too long monopolized by the capitalist non-producers, party demagogues and speculators, to the exclusion of the people, whose rights are as dear and valid."

Bagley oversaw the publication of a regular “Female Department,” a section devoted to “women’s interests,” written entirely by the self-proclaimed “Factory Girls”. Under her direction, the Voice also became a principal advocate and organizing force for the Ten-Hour Movement in Lowell. In 1846, the Association bought the presses to produce the paper, with Bagley briefly assuming the editorial chair.

debate with the lowell offering

The paper’s focus on worker struggles and its defiant tone stood in sharp contrast to an earlier and more famous publication, the Lowell Offering.

The Offering, a magazine that published literary work by female workers, painted a sanguine picture of life in the mills, and rarely published pieces that described the ever-worsening conditions endured by increasing numbers of workers. The disconnect between these rosy images and the dismal reality of factory life alarmed Sarah Bagley, who began submitting articles to the Offering that were critical of the corporations.

All were declined. In a fiery public speech, a frustrated Bagley rebuked the paper for its deference to the mill owners, calling the it a “mouthpiece of the corporations.” The speech set off a bitter debate about censorship and the role of the press with the editor of the Offering, Harriet Farley, who was herself a former textile operative. (The debate can be found in “Lowell Offering: Mouthpiece of the Corporations?”)

changes and iterations

For much of its existence, the Voice’s circulation was large and ever burgeoning, despite corporate efforts to limit its spread (see “Selling the Voice,” a letter from Huldah J. Stone, who worked to solicit subscriptions from nearby towns).

Despite this, the paper remained in constant financial peril. In 1847, circulation declined under the editorship of the reformer John Allen, as the paper began to focus exclusively on the associationist movement. The paper’s original editor, William F. Young returned to the helm briefly in an attempt to increase circulation, but his efforts failed and the paper ceased publication in 1847. (See “Editors and Honorable Mentions" for the reactions of other newspapers to some of these changes.)

In October of the same year, the Voice was resurrected as “An Organ of the People,” edited by D.H. Jaques, with a focus on Cooperative reform movements. In December it moved to Boston, where it advocated for Land Reform, before again becoming insolvent in April 14, 1848 (a shortfall of $350 stilled the presses). Its final incarnation was as “The New Era of Industry,” which published from June to August 1848. (These iterations of the paper can be found in the “Complete Issues" section.)

-

*The historian Norman Ware notes that the Voice had a growing list of “two-thousand subscribers," when Young retired in 1846, and was one of the “longest-lived papers of the period." According to another labor historian, Phillip Foner, it was the “most widely read and influential labor paper of the 1840s." (see Ware's Industrial Worker, pp 212-213, and Foner's Factory Girls, p.142.). Against this, Martha Mayo, head of the Center for Lowell History, has found that some of the paper's own published lists show no more than 100 subscribers. This difference might simply reflect the popularity of the paper at different points in time. What's clear enough, however, is that the paper was significant enough to merit the attention of several other newspapers of the day, including the New York Tribune, the Pittsburgh Dispatch, the Ohio State Tribune, the Manchester Messenger, the Chronotype, the Lowell Courier, the Lowell Gazette (see “Honorable Mentions I and II" in this section.)