History & Resources

When we think about worker unrest during the Industrial Revolution, the image that comes to mind is that of the tired, physically debased worker forced to endure long hours in overheated factories, and for a pittance. In retrospect, we rightly see these circumstances as deplorable. It’s often said that we can take comfort from the fact that these conditions were temporary, and that these losses were eventually balanced by the society-wide increase in wealth that resulted from industrialization. Whatever debt was accrued in the grim factories, in other words, has long since been repaid by the gains made.

This historical math would be compelling if workers' gains and losses were of the same kind. But they weren’t. The loss that workers were most concerned about during this period wasn’t material, but social. They were alarmed by a dramatic loss of status and independence, as control over economic life passed to large corporations and they were made to sell their labor for a wage. While it’s true that workers protested poor factory conditions, lower wages and longer hours, these were seen as symptoms of this more fundamental kind of degradation. It was, in short, a kind of loss that could not be offset by any future material gains.

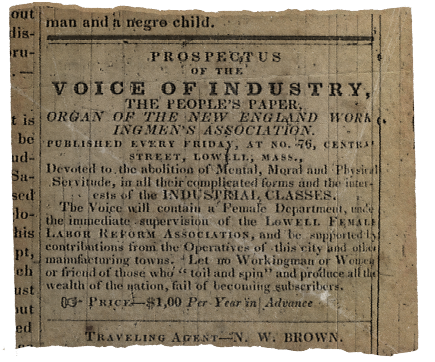

the voice of industry

It was within this context that the Voice of Industry, a worker-run newspaper, began publishing. And it was with this loss of status and independence that the workers writing in the paper were primarily concerned.

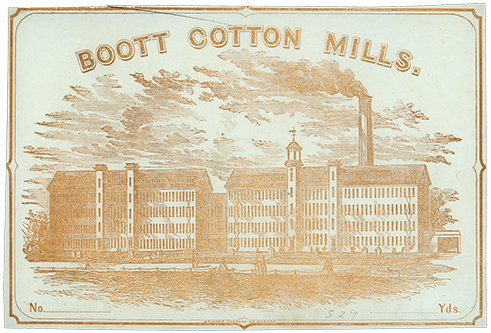

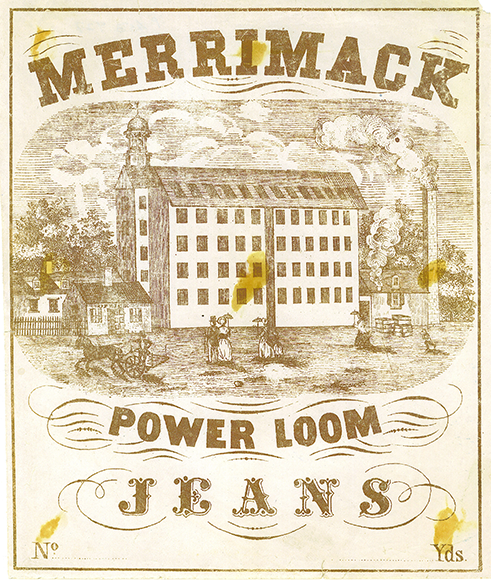

Founded at the height of the Industrial Revolution, and quickly adopted by young American working women, the Voice established itself in the “City of Spindles,” Lowell, Massachusetts. Lowell had been carved out of the wilderness by textile companies twenty years earlier, and had become the centre of the Industrial Revolution in the United States. It was also the site of many of the fiercest protests against the dramatic social reconfiguration spawned by the Industrial Revolution.

The prospectus of the Voice, declaring the paper's devotion to “the abolition of Mental, Moral and Physical Servitude, in all their complicated forms." From an 1846 issue.

criticism of the industrial revolution

Workers writing in the Voice were sharply critical of the industrial revolution and its attendant, rapidly advancing economic system, which we today call capitalism. They were particularly appalled by the character and effects of it's central, driving feature: an insatiable, selfish drive to accumulate wealth.

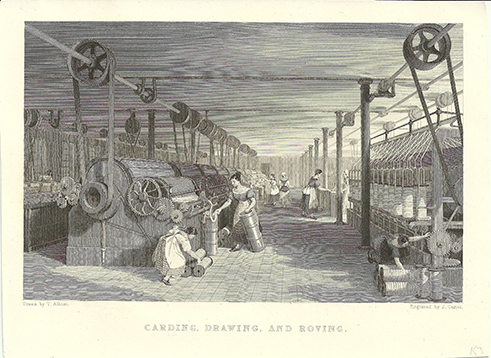

Accordingly, their criticism spanned a broad range. They denounced the ethic of selfish individualism itself, arguing that it was both immoral and destructive of the benevolent parts of human nature. They expressed alarm at how the profit motive distorted technological change, as new large-scale ‘labor-saving’ machinery, which might have been used to reduce their toil, was instead used to increase output. They protested the new ways of organizing work, which, in the name of maximizing profit, was divided into confined, repetitive tasks that diminished their capacity for self-development. They were dismayed by how economic power infected the political system, making reform efforts difficult. And all of this, of course, was in addition the harsh disciplinary power wielded by the corporations directly, which worked to worsen their position amidst unprecedented corporate prosperity.

american ideals

Significantly, many workers saw the new, profit-driven economic system as being opposed to traditional American ideals of freedom, justice and independence. This was especially true of the women writing for the Voice, some of whom were granddaughters of American revolutionaries, and self-identified as “Daughters of Freemen.” They shared a strong sense of dignity and social equality, and stubbornly refused to see themselves as less than equal to the mill owners.

This strong spirit of social equality had played a significant factor in the strikes of the previous decade, which were prompted by repeated wage cuts. In 1834, in response to one of these cuts, a petition that was signed by 800 women operatives concluded with the following poem:

Let oppression shrug her shoulders,

And a haughty tyrant frown,

And little upstart Ignorance,

In mockery look down.

Yet I value not these feeble threats

Of Tories in disguise,

While the flag of Independence

O’er our noble nation flies.

This content on this site is divided into twelve sections, across which the history of the Voice is distributed. Some of these reflect major themes and lines of criticism, while others deal with specific issues or events. Each section contains a brief historical sketch, to help put the material in context. (These introductions, as well as the historical note above, draw heavily from Norman Ware's The Industrial Worker and Thomas Dublin's Women at Work.)

-

The story of the working women of Lowell - who they were, and why they came to work in the mills - can be found in the introduction to the Rights of Women section.

Writing about the Female Labor Reform Association, the first labor association of women in the United States, can be found in the Political Economy section; the Voice and Rights of Women sections also include material about the Association.

Perhaps the most trenchant criticisms of the new capitalism expressed by workers writing in the Voice can be found in the Political Economy, The Life of the Mind, and Human Character sections.

Image Gallery

1 - 17

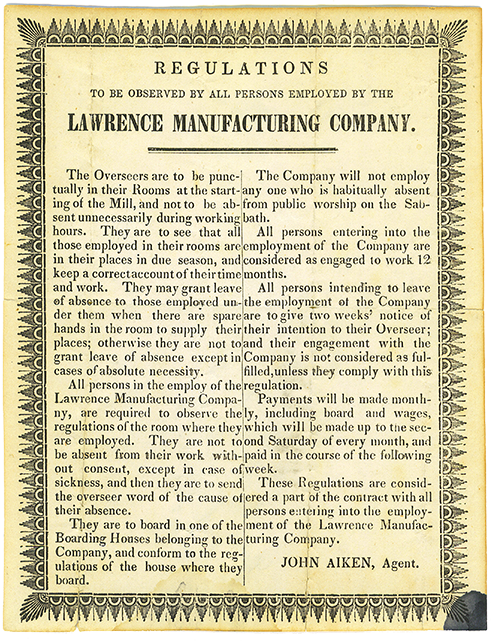

Regulations to be observed by all persons employed in the factories of the Middlesex Company.

(printed, 1846)

image courtesy of the

American Textile

History Museum.

Use of this material is strictly prohibited without the prior written permission of the American Textile

History Museum.

<

>

Books

For those interested in the working class reaction to industrialism in the period the Voice appeared, Norman Ware’s The Industrial Worker remains the best general introduction. (The working women of Lowell, and the Voice of Industry, are featured prominently.) Readers looking for a more detailed account of the history of the Mill Girls will enjoy Thomas Dublin’s Women at Work.

The “General Interest" list features books about related themes and issues. Jonathan Rose's Intellectual Life of the British Working Class is a stunning account of working class intellectual culture in England. Robert Heilbroner's The Worldly Philosophers is recommended for readers who want to learn more about the ideas of Adam Smith, and other thinkers that inflenced the reform movements of the period.

The Industrial Worker

Norman Ware

Women at Work

Thomas Dublin

For more about the nature of women's work, we would recommend Professor Dublin's

“Transforming Women's Work"

Factory Girls

Phillip S. Foner

Aspirations and Anxieties

David A. Zonderman

The Lowell Offering: Writings by New England Mill Women (1840-1945)

Introduction and Commentary by Benita Eisler

General Interest

The Making of the English Working Class

E. P. Thompson

The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes

Jonathan Rose

The Wordly Philosophers

Robert Heilbroner

Videos

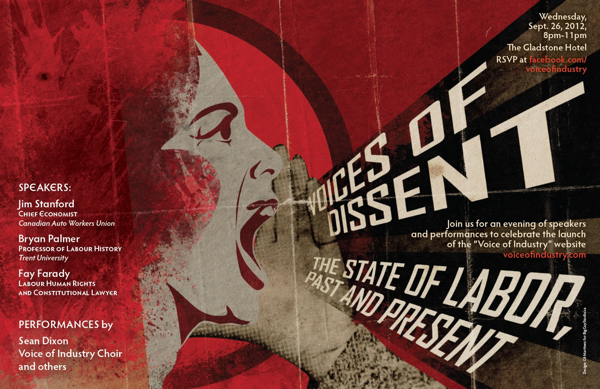

To commemorate the new Voice of Industry website, a number of speakers and performers participated in an event called “Voices of Dissent," which was held in Toronto on September 26, 2012. Videos from the event can be found below.

The Lowell Mill Girls: A Brief History

bryan palmer • lecture

An enlightening lecture given by Bryan Palmer, Professor of Labor History at Trent University, on the women who came to work in the Lowell Mills.

Click here to watch on YouTube.

kierston tough • performance

A moving performance by actor Kierston Tough, of “Voluntary?", a piece published in the Voice on September 9, 1845. The original piece can be found here. (Note that while the video cites Sarah Bagely as the author,

it was in fact written by Charles Dana.)

Click here to watch on YouTube.

the voice of industry choir • performance

A performance of the “Song of the Spinners," a choral piece about women working in the cotton mills. It first appeared appeared in the Lowell Offering, and later in the Voice of Industry. The original piece and lyrics, can be found here.

Click here to watch on YouTube.

The Current State of Labor

jim stanford • lecture

A talk by Jim Stanford, Cheif Economist for the Canadian Auto Workers Union, about the current state of labor. (Video Coming Soon.)

Links

Center for Lowell History

The Center's site has maps, images, photographs and material about mill life in Lowell.

Sarah Bagley

More about Sarah Bagley, by Martha Mayo,

head of the Center for Lowell History

Women and Social Movements

in the United States

A resource for U.S. women's history,

founded the historian Thomas Dublin

American Textile Museum

Located in Lowell, the ATHM “tells America’s story through the art, history, and science of textiles."

-

Zinn Education Project -

Industrial Revolution

A number of resources for teachers

related to the Industrial Revolution